Welcome

Welcome to this guide on how to write a PhD in biological sciences. I will not tell you what to write. My intention is to tell you how to approach writing with respect to style, format and formula (planning).

Writing a PhD is a daunting prospect. One does not put pen to paper, or, rather, finger to keyboard, only after finishing all of your experiments and/or labwork. Writing is actually something you should start from day one of your PhD, or even before day one, when you make the first initial pitch of big ideas to your advisor on what you want to do. If you can find the discipline to start writing from day one, then you are much more likely to make a much better go of it than waiting until the final, pressured, stretch. But to do this, you need to understand how to write a PhD thesis. You need to understand what you are aiming to achieve, and, crucially, you need to understand why you are doing your PhD.

This guide intends to demystify the writing process so that the eventual goal is clear, and provide the necessary information on how to get there. It takes you from those initial ideas, all the way through proposal writing, posing hypotheses, testing them, and then how to write it all up.

This book started as a series of blog posts written by me for my students (john.measey.com/blog). I wrote them because I felt that I was repeating the same advice year after year. Instead of rewriting comments on manuscripts time after time, I decided to consolidate them and put them all in one place. Later, I started looking for particular problems that students were having, and then writing blog posts to try to pre-empt those problems, and to provide solutions before tasks were completed. Finally, I have tried to fill in the missing gaps in the blog posts. But there are still plenty of gaps, and I regard this book as a work-in-progress. It is my intention that this book will always be added to, and improved by a community of practice, and I hope that this will include you.

Why read this book

Embarking on a PhD is intimidating as, for most students, it will be their first experience working within the academic system. The voyage of discovery is often made very frustrating as much of what goes on in academia is assumed knowledge. Academics accumulate knowledge throughout their careers, but what can be done for those who are uninitiated? What is needed is a guide that postgraduate students can refer to before, during and while making decisions about their time within academia. Note that this is not a rulebook. Your university, faculty and department will all have rule books that you should obtain and become familiar with. This book does not replace these rule books. Instead, this guide tries to explain how to achieve your goals of getting a PhD. There are times when this guide will be accurate and others when it will be vague, but providing some insight to point you in directions where you can explore more. The intention then is to provide you with a starting point from which you can establish your confidence in the academic writing process, and build your own creativity.

Structure of the book

This book is intended to be a guide. Originally, I called it the ‘Fool’s Guide to Writing a PhD in Biological Sciences’, but that didn’t fly. Don’t sit down and read it from cover to cover. If you do, then I think you have likely misunderstood what this guide is for. Instead, I want you to think about this book as a guide much in the same way that you might pick up a guide to a foreign city or country. However, instead of having hotels or restaurants recommended by name with a description of what makes them particularly praiseworthy, this guide provides a generic idea of what such places are for, what they tend to be like, the best ways to get to them, and pitfalls to avoid.

None of the topics is explored in any great depth. This is deliberate as this guide is here to provide you with a starting point for you to explore if you think it is necessary. I have provided literature (where possible), and you should use this in the standard way to research the topic yourself should you need or want to know any more. In the same way, none of the advice provided in this book should override what you decide for yourself or with your advisor. Take your decisions from an informed position.

The book is divided into four main parts:

Part 1 - Part one contains core skills that are relevant to all postgraduate students. These core skills are those that you will need to build upon from the very beginning of your studies. You are likely to already have some experience in some of them, but understanding how they fit together will provide a solid basis for your PhD process. Both critical reading and regular writing are core skills that you will need to develop from the outset of your studies. One of the most important aspects of doing a PhD is knowing what you want to use it for once you’ve completed it. Hence, this section of the book asks you to look not only at short term day-to-day planning, but also what you want to do after you’ve finished, pointing out that you will have opportunities to open doors during the duration of your PhD. At the start of your PhD is the time to be thinking of the bigger questions both in your study area, and your life, and this section provides some pointers and things to consider. Working within academia is particularly stressful, and students should be aware of the state of their mental health, how to measure it and determine whether it is deteriorating, and if so, what you can do to help yourself. I also encourage you to participate in the scientific project, and become aware of your role as a scientist within society.

Part 2 - Part two of the book sets out a practical guide to getting started with writing. The approach I’ve taken here is describing the production of a PhD in biological sciences which is made up of data chapters, and where each chapter is essentially a potential publication in a science journal. If you didn’t want to do a PhD but just wanted to write a publication, then most of what is here (and in Part 3) will be of use as you could take the same formulaic approach as given in this book. Similarly, if you were undertaking a MSc by research, this section would also be useful. The approach taken is ‘hypothesis-centric’, and how the entire chapter will be built around answering the hypothesis posed. This section explains how the hypothesis and all logical arguments that you make in the text are constructed from existing literature - standing on the shoulders of giants - with a practical guide on how to use citations. In addition to some nuts and bolts of how to write paragraphs, construct arguments, remain concise and avoid plagiarising, this section attempts to cover a lot of technical aspects of writing for the biological sciences.

Part 3 - A typical PhD will consist of five data chapters where each data chapter is a publication. The standard formula is to write this is in sections consisting of an introduction, methods and materials, results and a discussion. Together with the title, abstract, references and supplementary information, all of these parts also make up most scientific publications. In this section of the book, I go through each of these components using a formulaic approach. To get you started writing, I suggest how you can build each section from an outline that is fleshed out with literature and works around a hypothesis (from Part 2). In addition to the sections needed for your thesis, I also cover parts needed to submit a paper, including the title page, writing the abstract, supplementary material, authorship, and acknowledgements. Therefore, this part of the book will be relevant for anyone setting out to write a scientific paper in the biological sciences, especially if you are having trouble getting started.

Part 4 - The last and shortest section of this book talks about what you still need to do once your data chapters are written. For most PhD theses, you will need to write a short introductory chapter (sometimes a literature review) that comes before these data chapters, and a concluding synthesis chapter at the end. These chapters make your thesis into a ‘body of work’, and allow you space to reflect on what you have achieved in your PhD studies. I have framed their content at the bare minimum required, as many students will find themselves under a great deal of pressure to submit their thesis to a prescribed deadline. I also provide some alternative approaches for those who have the luxury of more time to attack these sections in more detail. The very end of the book sets out some reasons why you need to publish your thesis chapters.

Throughout this guide you will find links and references of articles to read elsewhere. The reality is that there is a lot out there for you to read. I am not the only person to write a guide, and I can’t pretend that all the answers are here in this book. You will find that in your particular situation you need to look around. What I aim to do in this book is provide you with enough background information to help in your onward search, and provide you with enough inside knowledge to do a PhD.

Why ‘A guide for the uninitiated’?

I think that most people with doctorates would agree that a PhD is not awarded to people because they are particularly bright or smart. If you had to be a genius then I wouldn’t have a PhD. Indeed, I don’t consider myself to be particularly clever, but I worked very hard to get my PhD. I was hampered by the fact that I didn’t know anything about the goals and aims of the academic process of working towards a PhD, so it took a lot more work, wasted time, and (let’s not mince our words) real pain. The end product was a fraction of the potential that I could have achieved, if I had understood more about the process. If I had only had a guide to tell me what it was all about, I could have saved myself so much time and energy. In short, I feel that I was uninitiated, and this is the guide I wish that I had had.

So, this guide is my practical attempt to help you to get the most that you can out of your PhD time. You will doubtless hear many academics referring to your PhD studies as the best of times. Their retrospective view probably won’t resonate with you as it’s easy to forget all of the hard work involved. But you can only make the most out of your time if you know what you are trying to achieve, and that is the aim of this guide. After all, yoru PhD should be an amazing journey of discovery that culminates with you achieving academic maturity: the ability to conceive and carry out scientific investigations. When you have a PhD, you become a scientist.

You should be aware from the outset that doing a PhD is a major undertaking. It will take several years of your life and will impact heavily on your day to day life, to the extent that your mental health may suffer. A PhD represents the culmination of an incredible amount of work, not to mention that you’ve already had to complete one to three previous degrees beforehand. It may not be something that you ever finish to your own satisfaction. But finish it you must.

What’s not in this book?

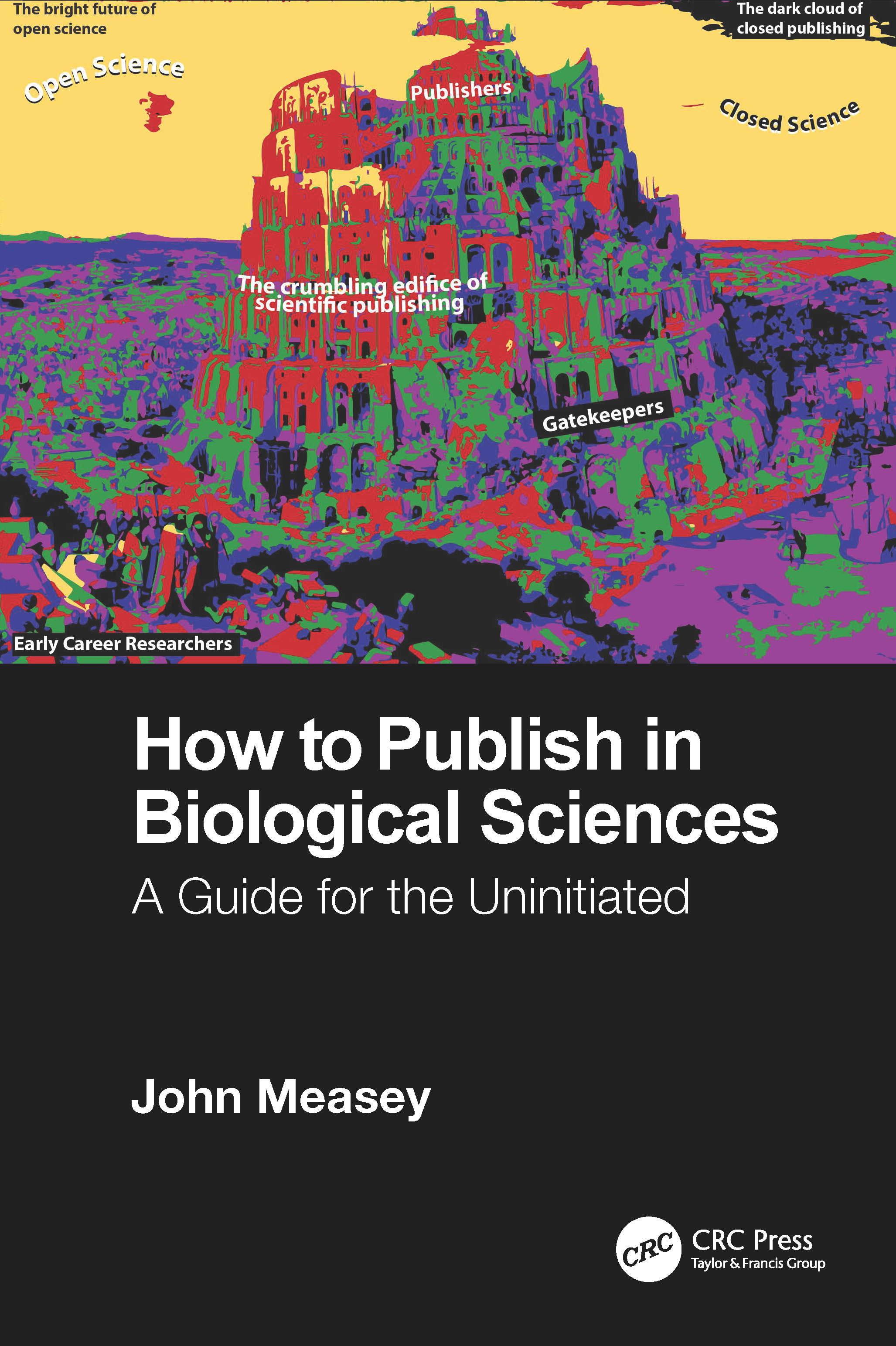

Depending on just how early you are in your career, there is a lot missing from this book that has been provided in another book: How to publish in Biological Sciences. That book concentrates on publishing manuscripts, while this book concentrates on getting students started writing data chapters. Hence, if you want extra information about publishing in the biological sciences, I would point you to the other book. If you are still writing and generating content then this is the right book for you.

If you want more help with publishing, and want help to demystify the publishing process, then How to publish in Biological Sciences has the content that you need:

There is common ground in both books, and I will point to important chapters relevant to publishing in the other book that are not reproduced here.

Acknowledgments

Before I go on, there are a great many people that I need to thank. First and foremost are my students, past and present, who have inspired me to put together first the blog posts and then the book. It is because you wanted more that I put this together. I have also been a student, and have been inspired by colleagues around the world who are exemplary advisors. This book contains lots of links to blogs and articles written and posted freely on the internet by others who also aim to demystify and help. I thank this greater academic community (especially #academicTwitter) for sharing and inspiring. Thanks go to the many reviewers and editors who have taken their time to improve my writing. I am still learning. Lots of the text in this book has been improved by feedback from my students and postdocs. A special mention must go to my brother, Richard, who has hosted my lab website for more than a decade, and especially for saving blog posts from hacking attacks. Thanks also to Thalassa Matthews, who proofread many of the blog posts after I had published them late at night, so that I could correct them over breakfast in the morning. James Baxter-Gilbert, Ellie Brown, Sebastian Chekunov, Jack Dougherty, Anthony Herrel, Andrea Hurst, Allan Ellis, Joe McArthur, Andrea Melotto, Max Mühlenhaupt, Lisa and Mark O’Connell, Claire Riss, Pat Schloss, Ben Stevenson, James Vonesh, Carla Wagener all read or commented on different aspects of the book. Thanks are also due to my colleagues at the Centre for Invasion Biology, the Department of Botany and Zoology, and in the library at Stellenbosch University.

John Measey

Cape Town