Chapter 10 Regular writing

This book is about writing your PhD in Biological Sciences. This chapter is about using regular writing as a core skill to improve your writing skills throughout the duration of your PhD studies. Writing is a core skill that you need to work on, and a regular writing slot is the best way to develop this skill. This chapter will be short because, unlike the other core skills in this section of the book, the rest of the book will go into scientific writing in detail and provide you with all the advice you need to get started writing.

Just like any skill, you can’t expect that scientific writing is going to come easily to you, and you need to invest time not only to learn how to do it (Parts II and III), but also to practice writing so that you implement the skills that you learn on a daily basis. Regular writing and implementing what you learn in this book will be the best way to improve your scientific writing skills.

10.1 Write every day

When you make your day-to-day calendar for your normal working week, I strongly suggest that you put a 40 minute block every day that you dedicate to scientific writing (i.e. thesis writing). Know what topic you are going to write about before you start, and make sure that you have already conducted the relevant critical reading to accomplish this. Start your 40 minute block by writing the outline of your work with a list of relevant papers to cite. Then concentrate for these 40 minutes on writing something that meets the goal you set.

You need to be realistic about what you can achieve in 40 minutes. Especially at the start of your PhD, you might not be able to write more than a few sentences or a paragraph in 40 minutes. At the very beginning you might even struggle to complete your outline. However, the discipline of dedicating 40 minutes every day to undistracted writing will pay-off over time.

Don’t expect perfection in these 40 minute sessions. Instead, concentrate on your plan and think about how to introduce (topic sentence), and logically link sentences that are backed up with citations. The first paragraph that you write may not be a keeper, but making that start is important as it will show you what you need to change.

Build on your paragraph, but don’t return to the same paragraph every day. It is important to change the writing topic often enough so that you don’t get stuck on a particularly difficult task. By changing the topic several times during your week, you’ll should find that it retains your interest. You can add plan in weeks to come to return to tasks that you are struggling with or which need more time to complete.

While I recommend that you write every day, I would stress that this means every working day. You should have a break for at least one day a week. You should also have some days every year when you have a holiday and others where you are doing other tasks, like fieldwork, that will preclude you from writing every day.

10.1.1 Remember your critical reading

Daily writing will go hand-in-hand with daily critical reading. Plan both of these activities in a complimentary way so that you have the reading foundation for what you plan to write. However, make sure that you mix it up so that you get some variety in what you are reading.

10.1.2 Reflection

Once you start writing regularly, you will find that you have ideas about how to solve writing problems and ideas about what to cite at other times during your day. Keep a ‘writing notes’ file or a page in your notebook where you can jot down these ideas, and come back to them in your regular writing time-slot.

As stressed in the chapter on health, time spent thinking and reflecting on many aspects of your PhD is very important. During your sleeping hours your brain will make connections between items and tasks that you have conducted during the day. Hence, it may be that it may be a only day or two later that connections become clear to you. These insights can be very valuable, so make sure that you keep a note of them and look into them further to see whether they are worthy or important. Remember that your brain can also make false connections, so not every idea will be a winner.

10.1.3 Use one of the best time-slots

When planning your regular writing, use one of the time slots when you know that your concentration will be at its best. Don’t use a time when you know that you are likely to be tired or unfocussed. The idea here is to maximise your ability to write, during these time-slots. In time, you may well find that as your writing becomes better you will need to dedicate the best time-slots to other priority tasks. But when you start, I’d advise you to begin by keeping the best time-slots for daily writing tasks and critical reading.

10.1.4 The space in which you write

You will see a lot of advice online about the writing environment. Essentially, this comes down to how the psyche works linking certain spaces with work and others with not working. For example, using the same space to try to work as you do for checking social media or playing games will build an association other than work with that space. This is not beneficial to working. So if you can, separate the places where you do your regular writing from those where you reward yourself.

10.1.5 When you haven’t read enough

At first you will not have read enough papers to properly plan or cite all the relevant literature for the paragraph that you aim. In these first few weeks, concentrate on some of the writing techniques that you are reading about (in this book and elsewhere) so that you get some practical experience of writing some logical sentences, writing hypotheses, etc. The point of making this daily practice in writing is to get yourself used to writing in a scientific way. You can start this from day one, only having read a few of the chapters from this book, so give it a go.

10.1.6 Don’t allow yourself to get stuck

The aim of this time is to actually write. What you don’t want to do is spend any time staring at a blank screen or constantly tweak a single sentence or phrase because you can’t get it to sound the way you want it. Remember that writing well takes practice, and that this session is focussing on the practice. You won’t get the sentence perfect the first time that you write it and so you should expect that what you write during this sessions is going to need more work. If you feel like you are getting stuck with your writing during a writing session, then highlight that sentence in a consistent colour for writing that needs work (e.g., red), and move on. Start writing a different sentence or paragraph.

In your next regular writing session you will be able to go back to these difficult phrases where you got stuck and give them another go. You may find that you immediately solve the problem (thinking time and good sleep do wonders for getting stuck). Or you may find that the problem is still intractable. If after a week of returning to the phrase/sentence/paragraph you are still stuck make sure that you put this aside and concentrate on another topic for the next week and don’t return to this one for a week or longer. Start again with the same outline of what you want to write and build it up without any reference to what you wrote before.

There is also an influence of your mental attitude towards writing. Never start a session thinking that you are going to get stuck, or that you can’t write. You can write. It takes practice and the practice takes time and that is the purpose of these time slots. If you find yourself getting into a negative frame of mind before you start your session, try repeating a positive writing mantra before you start.

I can write.

I will write.

Regular writing practice is what I need to improve my writing.

If you remain stuck after returning to it, then discuss it with people around you. You could also get inspiration from Artificial Intellegence (but don’t copy it) There’s always a way to solve issues when you get stuck, but some are definitely more tricky than others. Time (while you think about it) and input from others are usually sufficient to solve the trickiest of writing problems that get you stuck.

10.2 Aims and outlines

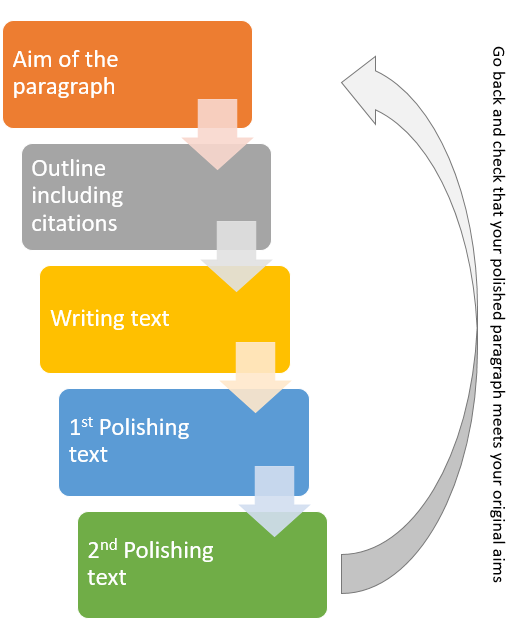

The aim of your writing session and an outline is a very important part of the writing process (Figure 10.1). You must make sure that you know what information you are trying to convey to the reader before you start. It’s best if you can write this aim down. This is important as once you have written your piece, you will need to polish and check it and then make sure that it meets your intended aim. If you don’t write down what you are trying to tell the reader, then it’s really hard to check that you have met your aim once you’re done. Writing easily becomes aimless, especially when you are building arguments and trying to include all of the citations that you need. Your topic sentence should keep you true, but an aim and detailed outline are even better for making sure that you’ve done what you planned.

FIGURE 10.1: Polishing and checking your text. The writing process includes a planning phase including the aims and outlining before the actual writing itself. Once you have written text you will need to polish it (perhaps many times) and then check that it meets your original aims.

10.3 Polishing your text

Once you get into the flow of writing, you should maximise this time within your 40 minute block. But if you have time, or in the next block, you also need to read through what you have written. I find that I need time between writing and reading. It could be a different time in the same day, or even the next day. I need the time because if I immediately read what I have just written, I can correct some spelling an minor grammatical errors, but I still feel too close to the composition of the writing to know whether it has the intended flow, and importantly, whether it meets the objective of what I’m trying to convey to the reader. If you have any difficulty reading your own text, then a lot of word processing software will now read it to you, so this is a very useful feature as you may be able to spot difficulties when you hear what you have written being read aloud.

Thus, reading what you’ve written will be an important part of each of your writing sessions. But it may be that you are reading what you wrote days or weeks before. I think of this process as polishing (Figure 10.1). Once I am reasonably happy with a section of writing, I know that it will need two or three polishing sessions before I think of it as finished - or at least good enough to share with co-authors, or in your case to show your advisor. It may be that when you start, you need more than two polishing sessions. That’s ok. Give yourself as much time as you need to get it to a point where you feel comfortable sharing it (with the caveat that you also need to know you have sufficient confidence).

10.4 Be disciplined

Make sure that the 40 minutes you have allocated to writing are spent doing writing tasks. If you fill your 40 minutes with reading, arranging your chair, screen, table then you won’t be helping yourself. Especially if you reinforce this by rewarding yourself it will actually cement these displacement activities instead of rewarding being productive. It will be up to you to decide whether or not you have achieved your goals.