Chapter 16 What’s the big idea?

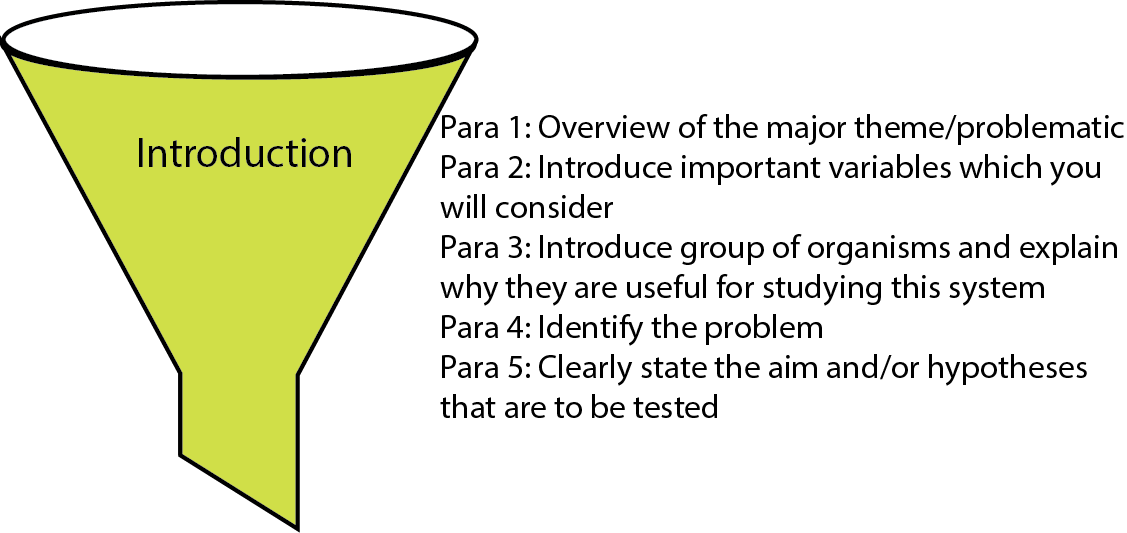

In the previous chapters, I’ve talked about the importance of having a hypothesis, and building that hypothesis in a logical framework within the introduction. The introduction serves to inform the reader about why this particular hypothesis was chosen, introducing both the dependent and independent (response and determinate) variables, as well as the presumed mechanism by which the hypothesis can be falsified (or upheld; Figure 16.1).

FIGURE 16.1: A framework for writing your introduction starts with the big idea and ends with the hypothesis. The funnel introduction is so called because it resembles a funnel in which you channel the reader from their own interest in a wider subject area into the relevance of your particular study.

16.1 So where would we find these big ideas?

It should come as no surprise to you that the big ideas that we seek can be found in the literature. Your challenge is to find the big ideas that apply in your own discipline. Although we cannot provide individual answers, there follow some ideas about how to approach these concepts, and practically go about finding the big ideas that are applicable to your study.

16.1.1 Tinbergen’s (1963) four questions

In his (1963) paper, Tinbergen posed four questions that he showed could be answered independently of each other, but that together could explain any observed biological trait. These questions are often laid out on a grid (Table 16.1) as this shows how they are pieced together to provide an explanation of the trait.

| - | Contemporary | Chronicle |

|---|---|---|

| Proximate | Mechanism: What is the anatomical or physiological structure of the trait? | Ontogeny: How does the trait develop in individuals? |

| Ultimate | Adaptive value: Why has the function of the trait influenced fitness? | Phylogeny: What is the phylogenetic history that led to the trait? |

Note that the first two questions are both proximate in that they explain the structure of the trait and its developed. The last two questions are evolutionary (or ultimate), to determine how the trait is influenced by selection.

Although Tinbergen (1963) originally conceived these questions to explore behavioural traits, these four questions are used more widely as big ideas that enable biologists to determine proximate and ultimate causes of any trait that they wish to study, either independently of each other, or in synthesis to provide an overall picture. If you haven’t done so already, it would be worth spending time to determine how many of Tinbergen’s four questions have been answered for your own study system.

16.1.2 A hierarchy of hypotheses

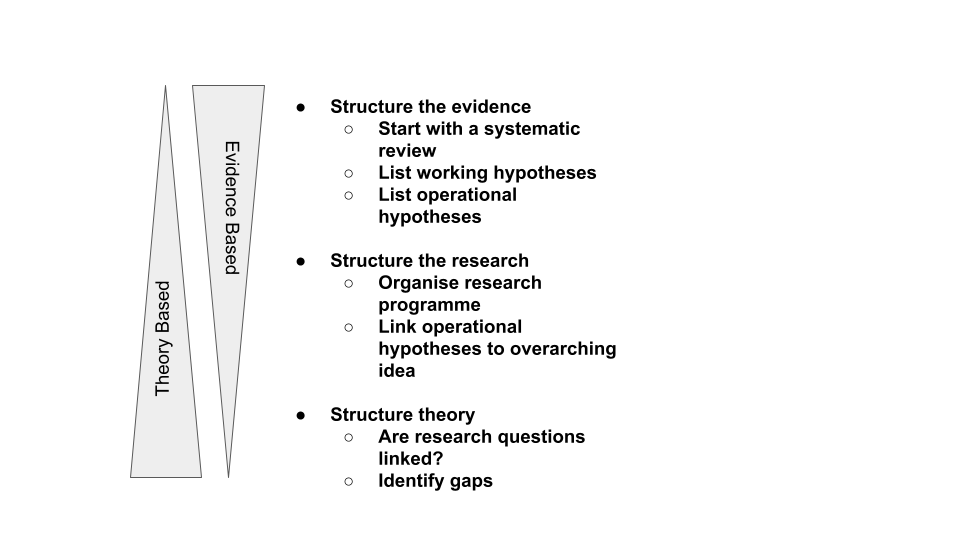

There are quite a few papers that synthesise hypotheses in various areas of biology. Here I provide a few to get you started. Ask your advisor about relevant reviews of hypotheses in your area of biological sciences. For example, here are some theories and hypotheses in ecology (Catford, Jansson & Nilsson, 2009; Vellend, 2010; Travassos-Britto et al., 2021), while these wide ranging papers about so-called ‘laws’ in biology and ecology (Lawton, 1999; Dhar & Giuliani, 2010). Each of these papers will give you a list of big ideas, together with the citations for seminal papers that have built them. Clearly, you will need to find the papers that set out these big ideas in your own discipline. You will note that many of the theories are very old, with some dating back to Darwin. You can think of the way that such ideas are structured as a hierarchy of hypotheses (Figure 16.2). Building such a hierarchy of ideas in your own specialist subject area is good reference material to prompt critical reading and reflection. You may want to take this structure forward when thinking how to introduce your PhD chapters.

FIGURE 16.2: A hierarchy of hypotheses can be used to help determine your Big Idea. A useful structure for thinking about how hypotheses are structured was presented by Heger & Jeschke (2018) in what they termed the Hierarchy of Hypotheses.

Of course, there are many ways to approach and test these theories, but if you don’t know about them, your work may actually make a considerable contribution to upholding or refuting them, but go totally unrecognised. When the significance of your work isn’t realised, it’s unlikely that it’ll be widely read and cited.

Let’s face it, if all the effort of the work that we put into papers is just going to get buried, then is it really worth it? The work that we do is also expensive, so making it as relevant as we can to as wide an audience as possible is something that we should be concerned about.

So, I encourage you to stand on the shoulders of giants (Figures 22.1 by using big ideas in your introduction. Make sure that the data that you collect can actually be used to respond to some of these big ideas. Then make sure that you cite them, giving them the importance that they deserve (yes, even as key words) so that others can find your work, and you might even find that one day, your work has shoulders that are broad enough for others to stand on!

The take-home message

Reading the literature can really expand your mind and broaden your horizons. When undertaking a literature review, take the time to think about not only what has been tested, but what could have been. Make a list of theories and hypotheses in your own field and try to rank them in a hierarchy.