Chapter 32 Making sure that you don’t plagiarise

Plagiarism is when you copy somebody else’s work. We’re most familiar with plagiarism of writing and these days this is especially easy with the copy and paste function. Whether the source is the internet, a published (or unpublished) paper, or a translation of something written in another language, if you copy someone else’s work and paste it into your own this is blatant plagiarism.

When finding that there is plagiarism, I find that most people are not even aware that they have plagiarised. I think that this is because at some point in the past they copied and pasted the work of somebody else into a document and this later became incorporated into their text without them being aware of it. If this is your style of writing, then I suggest that you move away from copy and paste mistakes as it can land you in a lot of trouble. Rather make your own notes.

Plagiarism is a problem because, essentially, you are taking somebody else’s work without attributing it to them. However, blatant plagiarism is only one of several kinds of plagiarism, and it is important that you know all of the different kinds of plagiarism so that you know how to avoid it. Studies of postgraduate students have found that although all are familiar with blatant plagiarism, more subtle plagiarism is not understood by all (Shen & Hu, 2021).

It is really easy to avoid plagiarism. Follow these three easy steps (Table 32.1).

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 |

|---|---|---|

| Read the text written by someone else from which you want to draw inspiration from | Make basic (not detailed) notes on this written work | Put the original work out of sight, and using only your notes write out your own work |

There is one final Step 4 to the above Table 32.1, and that is whether or not to cite the work that you have just used. Citations are the topic of another chapter (see here), and you should be familiar with what constitutes a citation and what doesn’t. If you are taking an idea that is first provided in this specific text, and you are re-writing that concept, then you will need to cite the original work. If you are using someone else’s writing as an inspiration for your own work, then it may or may not require a citation, and you will need to read the chapter on citations (see here) in order to judge.

Let’s try looking at an example:

Example: Darwin’s survival of the fittest

“It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent that survives. It is the one that is the most adaptable to change, that lives within the means available and works co-operatively against common threats.” ~ Charles Darwin (1859)

If you want to use Darwin’s idea, then you could re-write the concept above, but then you would need to cite Darwin for this idea. As follows:

My text: Darwin (1859) stressed that it is individuals that are most adaptable to change who will survive, rather than the strongest or most intelligent of the species.

But let us suppose that you came across this idea not from reading the original text of Darwin (1859), but from another author who was writing about the same concept.

“Darwin proposed that the capacity of organisms to produce more offspring that can be supported by the environment would lead to a struggle for existence, and individuals that are most fit for survival and reproduction would be selected through natural selection.” ~ Samuel A. Cushman (2023)

If this was the text that inspired you to use the concept, you should not cite Cushman (2023) for the idea, nor should you use any of his text. Instead, I’d suggest that you go back to Darwin (1859), and take your inspiration from there.

To take this to another step, I asked ChatGPT to rewrite the text of Chushman (2023).

ChatGPT text: Darwin suggested that when organisms produce more offspring than their environment can sustain, it triggers a competition for survival. Through natural selection, the individuals best adapted for survival and reproduction are favored.

While the text provided by ChatGPT is not wholly incorrect, there are some subtleties that are worth inspecting. For example, the term “survival of the fittest” was coined by Herbert Spencer (1882), not Charles Darwin and there is some consensus that Spencer’s (1882) use of this term was not completely aligned with that given by Darwin (Offer, 2014). It appears that Chushman (2023) linked Spencer’s term to Darwin’s (1859) concept by using the word “fit”, which is commonly the case. However, ChatGPT uses “best adapted for survival and reproduction” which is our modern definition for fitness, but not what Darwin (1859) originally wrote: “the strongest… [and] …the most intelligent”. The point here is that when you cite the original text, you should go back to this text, and seek out what the author wrote and intended, not a later citation or interpretation.

Next, when you are wanting to cite an original text, you are often interested in the variables that have been investigated in that written work (see Part II). In the example of Darwin (above) this would be the variables strength and intelligence, and if your variable was reproductive fitness you would need to explain how this was derived from Darwin’s (1859) original concept. Of course, you could opt to use the original text in quotation marks and cite the text (and page) where this was from. However, this is not always appropriate, so you should get used to writing your own text about other people’s findings, concepts and ideas.

The other point about the ChatGPT text is that while it does not plagiarise Darwin (1859) or Chushman (2023), we do not know if it has plagiarised other text from its input data: text from the internet which is mostly derived from original input by human authors (see chapter on AI here). Moreover, as increasing amounts of text on the internet will be derived from AI, we have no idea how skewed and misrepresentative AI generated text will become.

There is more to plagiarism than meets the eye, and it is important that you have a good understanding of what plagiarism is as many postgraduate students only appear to understand the most blatant kind of plagarism when making a verbatim copy of someone else’s text (Shen & Hu, 2021).

32.1 The different kinds of plagiarism

It is important to know what plagiarism is, so that you know how to avoid it. While almost everyone understands that they must not use other people’s work verbatim, it is also important to know that other more subtle forms of plagiarism.

32.1.1 Blatant or verbatim plagiarism

This is when you ‘copy and paste’ someone else’s work and pretend that it is your own. Note that even if you didn’t use the copy/paste functions, if you have incorporated someone else’s written work into your own text, then this is plagiarism. This includes using a translated version of work in another language.

32.1.2 Paraphrasing

Some students will copy an entire sentence and then change one or two words; this is known as paraphrasing and is also plagiarism. Subtle variations on this including switching the order of the clauses in a sentence and substituting some words with synonyms. The essence of paraphrasing is that you start with the verbatim form of plagiarism, and you are then attempting to engineer some differences by remixing this content. Instead you should take the three easy steps (Table 32.1) and write it yourself. Remember that you may need a citation (see above).

What follows are more subtle forms of plagiarism:

32.1.3 Failure to attribute

If someone else wrote pieces of your thesis and you do not attribute their input, this is plagiarism. There are many people that could help with your writing, such as friends, lab mates, or your advisor. But if you then pass this work off as your own, it is plagiarism.

With failure to attribute plagiarism, it is not as simple as stating that some text was written by your friend or lab mate. This is not an option. When you submit your PhD, you will declare that the work is your own and that you have written all of it.

There is another form of failure to attribute plagiarism when you employ a third party to write your thesis for you. This process is often referred to as a “paper mill” (Measey, 2022). Even if you paid this person and they gave you permission to use the text in your thesis, it is still plagiarism.

32.1.3.1 Is it plagiarism if an AI bot writes it?

I would also place the use of AI as a form of failure to attribute plagiarism. Currently, we are moving into the new territory of AI generated text. You can not use AI generated text (e.g. ChatGPT or Bard) in your PhD or in manuscripts submitted to journals as it is prohibited. Most institutions make you sign a declaration that you will never do this. You can read more on this topic in another chapter here.

32.1.4 Autoplagiarism

I would maintain that there is not really any grey area in plagiarism. So what are people talking about when they refer to a grey zone? The nominal grey zone within plagiarism comes when you copy your own text, this is sometimes referred to as ‘text-recycling’, ‘self-plagiarism’ or ‘autoplagiarism’. A new guideline from Hall et al. (2021) sets out the different types of grey plagiarism, or text recycling:

32.1.4.1 Developmental recycling

Developmental recycling is when you are reusing text that you have written for example between your proposal and something you intend for publication or in an ethics application that you also want to use in your thesis. All of this sort of developmental recycling is permitted and actually encouraged. I would further encourage you to use the opportunity of recycling this text to develop it and refine it further, condensing and improving where you can.

32.1.4.2 Generative recycling

Generative recycling is where you take pieces of already published text for example from the methods when it does not make sense to change the text or actually makes it more obscure to reword it in order to avoid plagiarism. In my experience this doesn’t amount to more than a few sentences describing technical settings on equipment. However this will depend strongly on your own subject area and may amount to larger chunks of text. I suggest that it is usually possible to reword most of the methods sections of papers. You should really only be generatively recycling material if you cannot avoid it: i.e. when the text becomes more obscure by your attempts to reword it.

32.1.4.3 Adaptive recycling

Adaptive recycling is where you are using published text as the basis for a different type of content (e.g. a popular article online, a magazine, or op-ed). I think that this kind of text recycling is quite unnecessary because you almost certainly need to reword your text for a different audience. There maybe times such as figure legends where you need to reuse text that was already published. If you do find yourself in such a position then check with the copyright owner of the material that you are able to reuse the text that you want without legal issues.

32.1.4.4 Duplicate recycling

Duplicate recycling (also known as ‘manuscript recycling’) is where large tracts of texts are essentially the same for the same message and audience. This is never likely to be sanctioned as it suggests that you are attempting to publish the same work twice. It will not be legal or ethical. Manuscript recycling is a bigger problem in other subject areas, notably economics (Geraldi, 2021), publishing issues in economics appear to need a lot more professionalism.

32.2 How to know if you have plagiarised

Today there are several pieces of software that are used to scan text that’s written and available on the internet to discover plagiarism. One such example is TurnItIn. One of the outputs of TurnItIn is to highlight text that matches other text already on the internet. As almost all journals publish on the internet, TurnItIn can accurately determine if text has been copied from another article or website. I usually set TurnItIn to determine plagiarism with five or more consecutive words.

Remarkably it is very difficult to come up with exactly the same words that someone else used to describe a phenomenon. Most people when they think about it feel that it wouldn’t be that surprising if they came up with exactly the same words as somebody else.

When caught plagiarising most undergraduates claim that they simply read an article and then later happen to write the same words that were in the article. They categorically deny that they ever copied or pasted text from the article into their work.

Try it. When you try it you will learn what plagiarism is all about.

Read an article, and then try to write text that is exactly the same as that in the article without looking back at the article itself.

Unless you have an eidetic memory you will fail at this task.

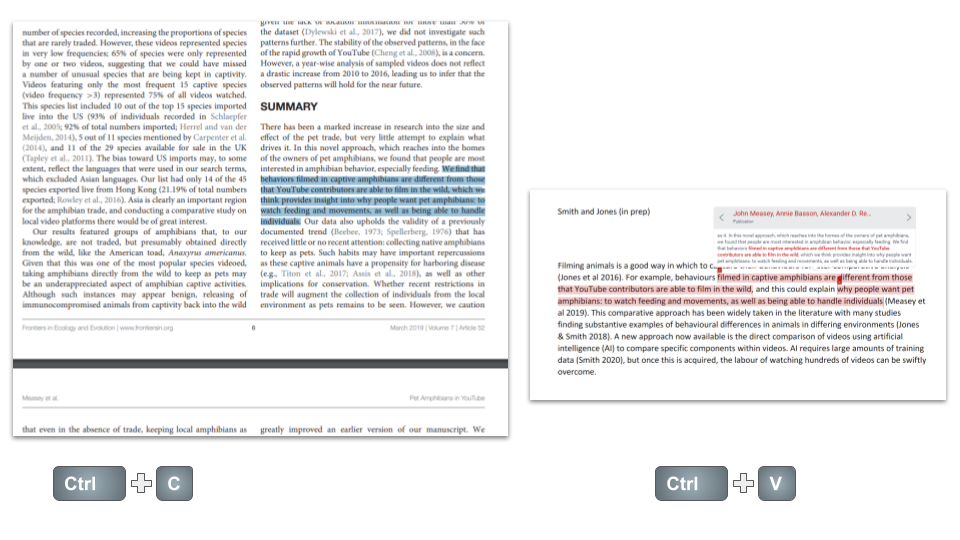

FIGURE 32.1: It’s always tempting to copy and paste, but it is likely to lead to plagiarism. Copy (Ctrl + c) and paste (Ctrl + v) have become so easy that it is tempting to pick up portions of appropriate text directly from papers and then slot them into our own work (Figure 32.1). However, this is plagiarism and can easily be found by using software like TurnItIn. Most institutions will require checks for plagiarism on your thesis after submission, with dire consequences if your text fails.

This is not to say that no 5 or more words can ever be the same as someone else’s. There are situations in which this happens. Think of addresses, quotes, certain laboratory equipment or protocols, and certainly references at the end of your paper. So there are many times when TurnItIn will come back with matching text. This is not what we’re looking for in plagiarism.

32.3 Free online plagiarism detection tools

If your institution doesn’t subscribe to a plagiarism tool, then you can check your work online free using one of a number of tools available. There are advantages and disadvantages to each, so I suggest that you try them out, and see which suits your needs best.

- Grammerly (www.grammarly.com) Checks your work for plagiarism for free, but you need to create an account (even for the free version) and you have to pay if you want it to check your grammar.

- Plagiarisma (plagiarisma.net) You’ll need to create an account (to see where your copied text came from) and paste your text into a box, but you’ll get a good sense of whether or not there is plagiarism in your text.

- PaperRater (www.paperrater.com) No need to create an account to paste text into a box (but it didn’t recognise my content which is also on my blog and so doesn’t get top marks from me). Some nice different output with suggestions on readability and grammar.

32.4 What to do if plagiarism is detected in your work

It’s remarkably easy to remove plagiarism from your work.

Here’s what you do:

- Read the sentence that has been plagiarised several times to yourself.

- Make a few notes about the meaning of the text, so that you don’t need to look back at it (avoid using the same words)

- Move the original text away so that you cannot see it

- Now without looking at that sentence, write another sentence that has the same meaning. Because it’s very hard to replicate somebody else’s words without copying them, what you should find is that you’ve written a fresh unplagiarised sentence.

- This can now be added to your text, changed as appropriate to fit your existing text. And that should be the end of your plagiarism worries.

This can be summarised into three easy steps (see Table 32.1).

Here’s what not to do:

- Take the sentence swap out some of the words for synonyms and pass it off as your own.

- The sentence will still have the same structure that you copied and, essentially, this is still somebody else’s work. Moreover, TurnItIn will still recognise this as plagiarism.

32.5 How can you make sure that you never plagiarise?

Quite simply, if you never cut and paste, you won’t plagiarise. It’s that easy. I understand why people copy and paste as a way to get started, or because someone else has written something so well, it’s hard to believe that you could ever write it any better. But actually, you can write it just as well, and writing it in your own words is worth so much more.

Don’t forget that the penalty for plagiarism in your thesis might well be that you fail. More than that, you could lose your place at the university or even your job (Ruipérez & García-Cabrero, 2016; Tatalović & Jarić Dauenhauer, 2017).

It still seems amazing to me when I submit a student manuscript to TurnItIn and see that it is completely free of any plagiarism. There are so many words in English, and so many different ways of putting them that you really can have your own writing style. Your writing style will be as unique to you as a fingerprint, and it will be entirely free of plagiarism. It’s something you can celebrate.

32.6 In summary - just don’t plagiarise

Plagiarism is the unattributed use of other people’s work. It is not simply the copying of other people’s text verbatim. There are many forms, and you need to be aware of the extent of that which is considered to be plagiarism in order to avoid it.

The simple way around plagiarism is not to copy any of your own text (self-plagiarism) or any of anybody else’s. This is, as I’ve explained above (see Table 32.1), relatively easy because as long as you use your own words, you should be plagiarism free. The temptation will always be great to go and copy the text that has been used before. But be aware that, however grey, this is plagiarism and you should not do it.