Chapter 7 Keeping track of your mental wellbeing

Stress is a natural part of life and many people are at their most productive when they are under some degree of pressure, such as a deadline. Although deadlines don’t work for everyone.

Douglas Adams famously claimed:

“I love deadlines. I like the whooshing sound they make as they fly by.”

Problems arise when we become overwhelmed by stress and are unable to fully respond. When this occurs, productivity can drop off and survival responses can be triggered as if responding to an actual physical attack. These responses include fight, flight or freeze responses. Anxiety and panic can be triggered. In this state, additional demands on your time may also push your life off balance, so that you start to neglect your personal well-being which can negatively impact on relationships, exercise regime, or even nutrition and personal hygiene. Some people can find that the additional stress can cause physical symptoms that may even need medical treatment (see Zhong et al., 2019). Your sense of competence and mastery can be negatively impacted such that you may even suffer from feelings of inadequacy or imposter syndrome (see part 2). These types of pressure tend to be low at the start, and increase during your time as a postgraduate student (Cheng et al., 2020).

Although there are not many studies on mental wellbeing for PhD students, those that exist (as well as surveys: Nature 2019) all suggest that there is a significant toll, which is proportionately higher than for others in society (Levecque et al., 2017). Whatever your prior experience of stress in a working environment, academia is known to be particularly stressful, and as a PhD student, you are likely to absorb a significant amount of this stress into your own life (Stubb, Pyhältö & Lonka, 2011; Cheng et al., 2020).

7.1 General Health Questionnaire

The General Health Questionnaire (see GHQ-12 in Table 7.1) is an instrument used to measure psychological distress. It is quick, reliable and simple to score, so you can use it at any time during your PhD studies as an indicator of whether you need to reach out to personal, occupational or professional support networks.

Right now, I suggest you complete the GHQ-12 (Table 7.1) and record your answers as a baseline. Keep the scores somewhere safe. During the course of your PhD, if you feel that your scores may have changed, take the test again and compare them with your baseline scores. Although there are no hard rules, if three or more of your scores have moved by two or more points it could be worth discussing with your support network to help you decide whether or not to seek professional help.

| General Health Questionnaire: Have you recently… | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| been feeling reasonably happy, all things considered? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

| lost much sleep over worry? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| been feeling unhappy and depressed? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| felt you couldn’t overcome your difficulties? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| felt under constant strain? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| felt capable of making decisions about things? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

| been able to face up to your problems? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

| been thinking of yourself as a worthless person? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| been losing confidence in yourself? | Not at all | No more than usual | More than usual | Much more than usual |

| been able to enjoy your normal day-to-day activities? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

| been able to concentrate on whatever you are doing? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

| felt that you are playing a useful part in things? | Better than usual | Same as usual | Less than usual | Much less than usual |

Even if you don’t feel you need the support of your institution now, it is worth finding out how they can support your mental wellbeing in the future if needed. Although there has been some stigma attached to difficulties with mental wellbeing in the past, most institutions accept that pressures are mounting on postgraduate students and that they may require support. Most institutions have experienced councillors available to support you if needed. Importantly, you should realise that none of these symptoms are unusual and that there is a high probability that many of your colleagues may also be struggling. Knowing that your problems are shared and reaching out to support networks early is an excellent way to prevent them from escalating beyond your control.

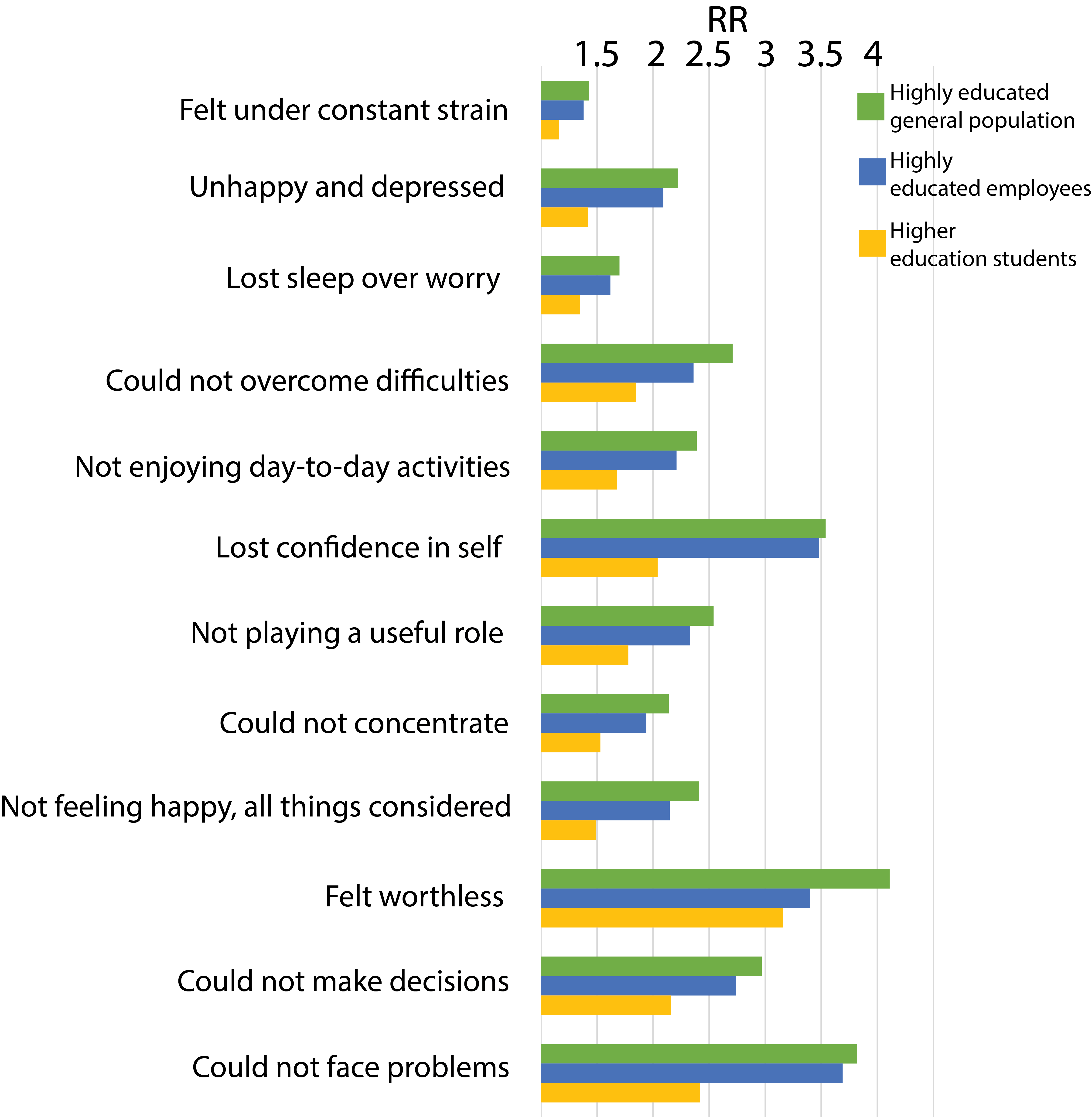

A study into the mental wellbeing of PhD students in Belgium exemplifies the kinds of difficulties that they face when compared with other similar groups (Levecque et al. (2017); Figure 7.1).

FIGURE 7.1: How does the mental wellbeing of people in different sectors compare? A comparison of the mental wellbeing of PhD students (data from Levecque et al., 2017) with highly educated general population, highly educated employees and higher education students using the General Health Questionnaire. The Risk Ratio (RR: adjusted for age and gender) in PhD students in Flanders, Belgium, is consistently higher (>1) when compared to any of the other surveyed groups.

No matter how well you think of your own abilities to cope with mental wellbeing issues, doing a PhD will cause you additional stress and can trigger maladaptive coping mechanisms. Learning how to cope with additional stress early in your career can be beneficial for future personal development.

Academia is recognised as a particularly stressful environment; you will likely take on some of this environmental stress in addition to any stress associated with your studies. Additional stressors come from home and family situations. Your best means of coping will be to try and develop a support network and to understand where and with whom you can discuss any difficulties as they arise. Knowing who this is and how and when to approach them will put you in a stronger position if you need them in future.

7.2 Support network

The people in your life make up your support network. Each person will have a different role, and not everyone in your support network will be able to support your mental wellbeing. For example, some of your colleagues at work might be in your support network for using equipment or doing statistics, but you may find that these same people do not necessarily understand you as a person. People in your support network for your mental wellbeing are likely to consist of your close friends, family and those colleagues at work that you find a special connection with (i.e. new friends).

You should identify your support network, and even place a tag next to their name in your contacts. Once you know who they are, you should also let them know that they are important to you, and that you may in future come to them to discuss issues around your mental wellbeing during your PhD studies in the future. It is important that they know that they have this role for you, and more often than not you can offer to fulfil this role for them in a reciprocal manor.

During the course of your PhD, you should make sure that you take the time to check-in with your support network and let them know how things are going. This means sharing the good times as well as the bad times with them. If the only contact you make with them is when things get really bad, you are likely to find that they don’t have a sufficient connection with you to help get you back on track. When you make contact with people in your support network, don’t forget that they also require support from you. Inquire about how they are doing and be prepared to spend time sharing your respective highs and lows. On each occasion that you invest time in your support network it will grow that relationship and deepen the level of mutual support that you can hope to receive when you need it.

7.3 Being physically active improves mental wellbeing

The positive relationship between the amount of physical activity and higher mental well-being is well established (e.g. Gerber et al., 2014; Grasdalsmoen et al., 2020), but the kind of exercise required to achieve this improved result is varied. For example, a study of college students showed that an hour of Thai Chi twice a week for 3 months was enough to have significantly improved physical and mental wellbeing scores (Wang et al., 2004). Increased levels of physical activity were also found to be associated with improved sleep quality in another study (Gerber et al., 2014; Ghrouz et al., 2019). There are plenty of studies out there that suggest there are multiple benefits from physical activity.

If you don’t do it already, then when you start your PhD also start regular exercise. Getting fit was the best thing I ever did to improve my work. The first thing I found was that I could sit and concentrate on work for longer. Before I got fit, I was constantly distracted and needed to take lots of breaks. Now I find that my concentration is much better and that as my fitness stamina increases, so too does my ability to concentrate.

It is important to note that exercise is not about creating some perfect body image that you might see on social media. A useful tool to help think about the importance of exercise for your body came from from Stutz and Michels’ (2022) Life Force model in which they proposed that your life force is equivalent to a pyramid. The bottom of the pyramid represents your relationship with your body which is equivalent to 85% of the life force pyramid area (Figure 7.2). Working on this component consists of sleep, diet and exercise. The second part of this pyramid has your relationships with other people, both personal and in your work context. Lastly, your mental wellbeing (your relationship with yourself) sits atop these other components and is supported by them. Working on the lower components of the pyramid will support your mental wellbeing, but you can also work directly on your mental wellbeing through, for example, mindfulness and meditation. Stutz goes on to explain that writing is a way to enhance your relationship with yourself. This might explain why some people find writing their thesis a very positive experience, but also gives us another way in which we can think about writing and ourselves.

FIGURE 7.2: A model to understand the importance of your body in connection to your mental wellbeing. In this model from Stutz and Michels (2022) you see the body taking up 85% of the area of the pyramid, on which rests your relationships with other people and finally your mental wellbeing on top. Maintaining your mental wellbeing therefore rests on your body receiving enough sleep, a good diet and exercise.

7.4 Valuing your sleep

Sleep is often underrated. But sleep research is showing us just how critical good sleep is for our health, including our mental wellbeing and many other aspects of what we are trying to achieve during our time spent not sleeping (Walker, 2017; Ramar et al., 2021). For example, student symptoms of anxiety and depression are commonly associated with poor sleeping habits including sleep that is too short or irregular sleeping hours (Becker et al., 2018a).

Sleep is a biological necessity, and insufficient sleep and untreated sleep disorders are detrimental for health, well-being, and public safety.

Kumar et al. (2021)

My point here is that you do not only need sleep for your general wellbeing, but it is also vital when you are studying, particularly during your PhD, as this is the time that your brain will be making and reorganising the connections between neurons to make sense of the day’s information (MacDonald & Cote, 2021; Miao et al., 2023).Hence, you need sleep in order to process what you have learned during the day. This is especially important for your critical reading and regular writing, because it is during REM (rapid eye movement) sleep that the connections between what you read and what you write will be made. This is why it is often a good idea to have some time between your first and second drafts of written work, because you will have the time to reflect and REM sleep to consolidate connections that were not previously there.

Keeping a notebook and pen by your bed could bring great rewards. Because you become concious of ideas and potential solutions between different sleep phases, it’s a great idea to have a notebook handy to jot these down. This has two functions, it will stop you obsessing about the idea and potentially losing sleep and ensure that you do not forget potentially useful ideas. Note that not every idea that you have is going to be a winner. But they are all worth keeping and considering the next day. Although it’s tempting to use your phone to capture such ideas, you should be aware that night-time use of screens is linked to sleep problems (Mireku et al., 2019), and could also distract you (with notifications) away from getting the sleep you need.

If you didn’t realise already, you need to be aware that regular sleeping with adequate duration is necessary in order to stimulate the REM sleep that you need to process all of the information that you take in during the day. That’s not to say that you can’t attend parties that go on late into the night - these are important too. But the majority of your nights should be spent getting sufficient and regular sleep. Good sleep will improve your studies, your mental wellbeing and your ability to take on the challenges of your PhD.

If you are experiencing difficulty sleeping, then there are many potential causes, and you can find out more here or watch this video. Happily, there are many things that you can change that will improve your chances of getting better sleep.

You would do well to consider the 5 principles for good sleep health (Espie, 2022):

- Value your sleep - recognise it for the importance that it has in your non-sleeping life.

- Prioritise your sleep - a regular sleeping pattern (time and duration) will produce better sleep.

- Personalise your sleep - the right sleep for you might be different for someone else and will change throughout your life. - Trust your sleep - will work for you and help you with your working day. The results of a good night’s sleep are not always evident in the short-term, but trust that they will bring you many benefits in the long-term.

- Protect your sleep - from degradation by keeping work and worries away from your sleeping environment.

I cannot stress strongly enough how beneficial good sleep is to your mental wellbeing, your PhD studies and your life in general.

7.5 Time to think

I used to think that the time I spent exercising was unproductive with respect to work. Now I have begun to realise that this represents some of my best thinking time. I use the time I spend trail running to turn ideas over in my head and especially to think through the logic in arguments, and potential flaws in experimental design. This isn’t to say that I don’t need to put time in at the computer writing it all down, or talking through ideas with colleagues. But I find the meditative time I spend exercising to be especially productive. Don’t take my word for it, see this great book by Caroline Williams (2021). In this book it is emphasised that exercise might not mean sport, but simply taking a walk or another aspect of self propelled movement. Actively seek out the activities that work best for you in order to think or reflect. Once you know what they are, plan to use them to optimise your thinking time.

7.5.1 Mindfulness

Mindfulness is the practice of bringing one’s attention to the present moment, being fully aware of thoughts, feelings, bodily sensations, and the surrounding environment. Mindfulness has been growing in prominence in the 21st century often eclipsing the more traditional practice of meditation. Although meditation and mindfulness share many techniques and benefits, the latter benefits from being able to conduct it anywhere and in any state and does not require specific time or space. For example, mindfulness can be practiced when walking home from work, washing the dishes or eating your lunch, while meditation usually involves a specific quiet environment and sometimes particular physical positions. The benefits of meditation are widely appreciated and have found their way into most mainstream spiritual practices.

In a meta-analysis, mindfulness was shown to have measurable effects on reducing stress, have moderate effects on anxiety, depression, distress and quality of life (Khoury et al., 2015). Moreover, this positive impact of mindfulness has been shown in very short training periods of as little as four days (Zeidan et al., 2010). Mindfulness training is associated with structural and functional changes in the amygdala, a brain region involved in emotional regulation (Hölzel et al., 2010), also helping to reduce repetitive negative thinking (Jain et al., 2007). People practicing mindfulness have been shown to have greater attention spans and better working memory (Jha, Krompinger & Baime, 2007; Mrazek et al., 2013).

If you want to try mindfulness, or more formal meditation, there are many self-help books and other internet resources available. You can start by exploring these resources here, here and here.

7.6 Balancing work with life

Having already told you that doing a PhD might unbalance you mentally, regular exercise is a really good way to make sure that you retain that balance with life (see Hotaling, 2018). By life, I’m referring to everything away from your academic work. This might include family, friends, sport, hobbies (even fishing). If you don’t have friends outside your academic life, then it would be a good idea to find some so that you can keep in contact with the ‘real world’.

There are some extremely unhealthy workplace cultures around that encourage students to work from early until late, implying that unless you are seen at your desk that you cannot be productive. I have worked in these places and found them to be unproductive environments. If you are in such an environment, then you should be particularly careful about balancing work with life. You could find a role model who is living a better balanced working life, or push through with your own more balanced routine. When others around you see that you are more productive despite spending less time at your desk, you might be able to shift the culture into something that improves life for everyone.

Non-working time (e.g., holiday time) is also important in order to keep you productive during your PhD. You should not be working every day from beginning to end. Try to save at least one day every week work-free so that you can rest and spend time with friends and/or relatives. During busy times you might have to sacrifice this day, especially when you are working in the field or attending a conference. But you should make up this shortfall when times are less busy. You also need a real holiday when you take a break from your PhD work altogether at least twice every year.

It can be hard to switch between work and non-work time, and being able to do this will take practice. Because the period of your PhD is normally very intense, finding ways in which to make this shift and practising them will be a critical skill that you’ll be able to carry with you throughout your life. One suggestion is to finish your working time, whether this is when you leave your desk at the end of the day or just before you go on holiday, by regularly spending a final 10 minutes to list down the ideas and points that need attention when you come back to work. You could think of this as a shutdown routine, in the same way that you shut down your computer you are also shutting down your working time and switching into non-working time. By practising this technique, you will teach yourself how to switch from working into non-working modes. The great advantage of this technique is that you can combine it with your day-to-day time management planning so that these tasks and ideas fit appropriately into your scheduled activities and don’t impinge on your established working routine.

If you already exercise, then you likely know how important this is. But if you don’t then, my best advice (above anything else that you might read in this book) is to start as soon as you can. Do whatever is right for you. If you don’t already know, then try out different clubs or activities at your institution. There are normally lots to choose from. Make sure that you schedule regular time for your activity, even if that means that you run in the mornings before field work starts, or you spend your evenings doing tai-chi on the beach after a day at sea doing research on dolphins. Take your exercise with you wherever you go for your studies. Take it as seriously as you do your studies and you’ll find that both will benefit.