Chapter 4 Time management

How much time during the week do you spend doing nothing? Do your friends and colleagues ever find you sitting staring into space? My guess is that because you are starting a PhD, you are used to some level of time management and you can fill all of your waking hours every day of the week without the need for sitting staring into space because you have nothing to do.

We all have exactly the same amount of time in a day or a week. People who accomplish more in that time are doing so because they manage that time efficiently. You may well know such people and be amazed that they not only use their time at work wisely, but they also have time for sports, socialising and other hobbies. This is because once you have learned the skills of time management, including focussing on tasks that you have been assigned to do when you choose to do them, you’ll find that you can accomplish much more. Research has shown that time management is empowering having a positive relationship with job satisfaction and work-time balance and negatively with stress (Claessens et al., 2007). Moreover, postgraduate students who use time management techniques were found to have improved mental health (Liu, Song & Teng, 2023).

This chapter is meant to encourage you to manage your own time and help you start planning so that you can conduct all of the work needed for your PhD, and also find time for your life’s needs during your PhD studies.

4.1 Start planning your time today

At the start of your PhD, you are likely to have to attend classes, and so you will already have a fairly full time-table. This makes the task of planning your time slightly easier as you already know when you will be busy attending class. This period will give you a limited amount of free time (i.e., time that you have to manage), and you can start using this wisely to schedule both critical reading and academic writing tasks there.

4.1.1 Whole period planning

Once you know the subject of your PhD and what questions you need to answer with what experiments and observations, you will have to plan your remaining years of study to make sure that you can get all of these experiments done in the time allotted. Figure 4.1) gives you a visual idea of what this plan might look like. In addition to showing the time when you will be busy and on what tasks, it also includes goals and conferences. Of course, your own planning chart might look much more complicated and have many more rows of tasks to achieve. For example, you might want to split the time spent for each chapter by time spent acquiring data from that spent analysing and writing about it as separate rows.

FIGURE 4.1: Knowing when you are going to do the different work that makes up your PhD is critical. In this Gandt figure, I have broken the different tasks that are needed to complete a PhD into different chapters (rows) which include four data Chapters (C1-4) and a technique chapter (T1). For planning purposes over three years, I have split each year into quarters (Q1-4) shown as columns. In this example, collecting the data for the four data chapters is seasonally sensitive (data can only be collected during Q2), meaning that these are immediately prioritised for this work. The technique chapter involves intensive lab time, and so can be completed during Q3 and Q4. Also included are the goals for completing chapters (shown as yellow stars) and important conferences where the results of chapters T1 and C1 are presented. Also indicated is time to write the introduction (Intro) and concluding chapters (Conc).

However you choose to plan the period of your PhD, you will need a plan for the entire period that ensures that you have time to collect all of the data you need in the time you have available.

4.1.2 Day-to-day planning

Calendars are extremely useful for planning, and you should find that your phone or email app already has a built-in calendar that you can easily use. Web or cloud-based calendars are particularly good as you can access them from different devices and choose how they send you alerts and notifications for events. You probably already have one that you use, so I’d encourage you to keep using that same software and build on the framework you already have for your day-to-day planning.

When it comes to day-to-day planning it is really useful to know your own rhythms and abilities. Although everyone is different, everybody will have times in the day when they are more or less productive. I find that I can concentrate most in the early mornings while drinking a cup of coffee. Other friends do their best work late at night. Many of my colleagues sleep after lunch as their bodies concentrate on the serious task of digesting their large lunches. Becoming aware of your own best (and worst) times for concentrating is an important pre-requisite to your day-to-day planning as you will be able to set your best times for the work that requires the most concentration, like critical reading and scientific writing.

If you are new to time management, then what follows is a suggestion to get you started. However, there are many many different approaches and you should find what works for you.

- Add all current commitments (lab meetings, classes, etc.) to your calendar.

- Divide your day into 40 minute blocks. These are the blocks of time that you have to allocate to doing different tasks or assignments. The chances are that you already have commitments (such as classes), so you may have an existing framework of start and end times that fit logically for you. Of course, the time blocks don’t have to be 40 minutes - they can be longer or shorter. The aim is to find a period through which you can concentrate from beginning to end on a single task. If you can only manage 20 minutes at the beginning of your PhD, you will need to be extra strict with your time management so that throughout your studies you can slowly increase your concentration abilities up to 40 minutes and even beyond.

- Make a list of things that you find rewarding. Rank these from top to bottom with your favourite at the top. Examples might be playing a game on your phone, catching up with your instant messaging, drinking tea, going for a walk, having a snack or playing table-tennis. These rewarding activities will need to be achieved in 5 to 10 minutes, so don’t include things like baking a cake which would take much longer, which would require you to return home via the supermarket etc. You also need to consider that these activities should not rely on other people too much as their schedules may not match your own.

- Dedicate the 40 minute blocks to different tasks in your day. Focus on having regular tasks for skills such as critical reading and scientific writing. In the 5-10 minute gaps between the blocks allocate the best rewards (highest ranked) for the tasks that you like least.

- Plan for at least two weeks in advance, but also keep an eye on your whole period planning so that you know when you need to go to the field and accomplish your goals.

The idea of the above planning with tasks and rewards is to use motivation (Figure 4.2) to drive you to do the tasks that you like the least, and eventually to make them your favourite tasks. This is a really very simple but powerful way in which you can train yourself to manage your time, become more productive and start enjoying your least liked tasks the most.

FIGURE 4.2: Using rewards after doing tasks is a very easy way to manage your time enjoyably. Humans respond very well to rewards, and you can use this system to help yourself do your least liked tasks by rewarding yourself with your most liked activities.

My suggestion is to use colour coding in your calendar so that you can quickly see what you are doing next. You could use colours to code for the places where you will conduct each task block. For example, you could code your desk blue, the lab yellow and meetings red. This will allow a quick glance to let you know where you need to go between tasks. It will also determine the kind of environment that you need. Try to keep your desk environment for tasks that require concentration, and keep your reward environment separate. Associating certain spaces with different tasks and rewards will really help you quickly transition between roles when the time comes.

4.1.3 Remember to include time to be healthy

When planning your day, you do not have to include details like sleeping, eating, sports and time with your family and support network. However, as you get busier it is a good idea to make sure that you do have time to get adequate sleep, food and exercise time. There is research that shows that if you fail to get enough sleep or nutrition, post-graduate students cannot maintain their concentration on normal tasks, eventually leading to burnout (Renu & Dua, 2024). Hence, when you are especially busy, time management becomes a critical skill in order to ensure that you remain healthy.

4.1.4 Beware of displacement activities

These are things that you do that take up your time when you should be focusing on the work that you planned to do.

Common Examples:

- social media

- emails and correspondence

- direct messaging apps

- chatting with friends

- watching TV or listening to the radio

The danger with displacement activities is that they can become habit forming. Remember that social media sites are designed to take your time (for the purpose of you watching their advertisements). They are well-known to be addictive, and if you are already hooked the best way to manage them is to place your time on them strictly within bounds.

Learn to recognize displacement activities - once you know what they are either avoid them (if they are not productive) or carve out special time for them (if they are necessary).

4.1.5 To-do lists

Humans find it very satisfying to cross out tasks on a list once they are completed. Having a to-do list alongside your calendar might really help motivate you to a task based system of time management. You can write a list out for your week, adding items as they come up and crossing them out as you complete them. Then carry the uncrossed out items on the list over to the next week.

I encourage my students to have these lists in their meeting books so that we can check through them when we have student-advisor meetings.

To-do lists don’t work for everyone, so this is something that you might want to try and see whether it helps motivate you.

4.2 Multitasking (is a myth)

First, I am going to emphasise that the old idea of multitasking (trying to proficiently conduct several tasks at the same time) is a myth. Secondly, I am going to encourage you to multitask when the tasks that you are trying to accomplish are non-critical and do not require all of your attention.

Investigations have consistently shown that those who are trying to split their attention between two or more tasks do so at a cost to the tasks themselves (Gilbert, Tafarodi & Malone, 1993; Wang & Tchernev, 2012). For example, a study of students who were instant messaging while reading showed that this multitasking increased their reading time by more than 20% (Bowman et al., 2010). Similarly, trying to watch television while conducting academic work resulted in poor comprehension and memory recall (Armstrong, Boiarsky & Mares, 1991). The number of studies that show that humans are not capable of conducting several tasks proficiently at the same time is now overwhelming.

The above information should be of concern to us when we are conducting critical procedures that require all of our attention, such as driving a car, piloting a plane or conducting an operation. However, there will be tasks that you need to do that do not require all of your attention. Some aspects of your PhD might be incredibly boring and repetitive so you can do them with your eyes shut!

Your PhD will require a lot of activities that require 100% of your concentration. They will also have activities that require less of your attention. Know what these relevant tasks are and adjust your time accordingly throughout the day. High-concentration activities should be done when you are most alert. See below to see how to recognise this.

Low-concentration activities provide you with opportunities to conduct additional tasks. Note that although you can do different things at the same time, you won’t actually be multitasking, because your concentration will be flipping from one task to another constantly during this period. That’s why I’d advise only doing low concentration tasks together when your brain can cope with the constant switching.

Some examples might help. If you work in a lab where you need to fill pipette boxes or conduct a lab clean every week, schedule these tasks alongside a colleague and use the time to catch-up on their research and tell them how yours is going. This would be a more productive use of your time than listening to music. If you don’t have an appropriate colleague there, then consider downloading a podcast from your subject area, or an audiobook on something relevant. Be sure that you have note taking equipment close-by so that you can quickly jot down ideas as you are listening.

4.2.1 Priority activities

I cannot list all of the priority activities that you will need to perform during your PhD, instead I will list some general ones that everybody is likely to have. When you schedule time for these priority activities, you will not only need to put away things that might distract you from your task (such as a phone), but you should also try to clear your mind of worries and other aspects of your life that might impinge on this time. If there’s something happening in your life that you really can’t pull your mind away from, then it would be worth rescheduling any priority activities that you might have for that day. If such worries stretch for weeks or even months, then this is something that you should alert your advisor to.

4.2.1.1 Academic writing

Perhaps it is no surprise to find out that I consider writing a priority activity from which you should not be distracted (or attempt multitasking). For this reason, it is important to prioritise time for writing in your weekly schedule. Throughout this book I emphasise that academic writing is a skill that you need to practice, meaning that you can’t wait until the end of your PhD to start writing your thesis. Similarly, at the beginning of your PhD you should not expect to sit down and write perfectly. It takes time and practice, and this is why writing regularly is the best way to improve your writing skills.

Note here that I am talking about academic writing. I am not talking about writing an email or sending IMs to your friends. Academic writing, the subject of this book, is something quite different and no amount of writing IMs or emails will help you.

4.2.1.2 Critical reading

Like writing, critical reading requires all of your attention and is a skill that you will need to learn (see Part II). Critical reading is going to help the most with your writing skills, without actually writing. Of course, critical reading does involve writing, and I encourage you to read the chapter on this topic later in the book to find out more.

4.2.1.3 Meetings with your advisor

Your regular meetings with your advisor should be times when 100% of your attention is focussed on getting all of the information and advice that you need in the shortest time possible (see Part I).

4.2.1.4 Running equipment and machinery

Much of the equipment that you will use during your PhD will be very costly very likely accompanied with expensive consumables. Mistakes will happen, but if you break equipment or ruin consumables because you are distracted, then I don’t consider this a mistake, but your own folly. You now know that some tasks require all of your attention, and this will include many tasks involving equipment and expensive consumables. Give these the full attention that they deserve.

4.2.2 Non-priority activities

Having put together your timetable (above), you will already know what your non-priority activities are, because you had to find time to fit them in. My suggestion is to use a different colour for these tasks. They are the tasks that will drop away when you get especially busy, or have another additional task that you didn’t foresee.

Non-priority tasks are often important, but don’t need to be done immediately. Even if you post-pone tasks like these, it is a good idea to keep an eye on them to make sure that they don’t get dropped entirely.

These non-priority tasks will allow you to keep your calendar flexible so that you can accommodate additional or unforeseen tasks. Remember to make sure that your advisor agrees with you about what is a non-priority task. For example, if you consider lab meetings as non-priority and stop turning up, your advisor might not agree.

4.3 Time management hacks

You will find lots of advice out there on the internet about how to hack your time management and improve your efficiency. These ideas are numerous, and some are based on research that shows that breaking up intensive concentration time into short sessions followed by rewards is very efficient.

My suggestion is to give such hacks a go when you are not too busy. If they work for you, then that’s great. However, don’t rely on a hack that you have never used before during an especially busy time. During busy times you should be using tried and tested methods of time management that you already know work for you.

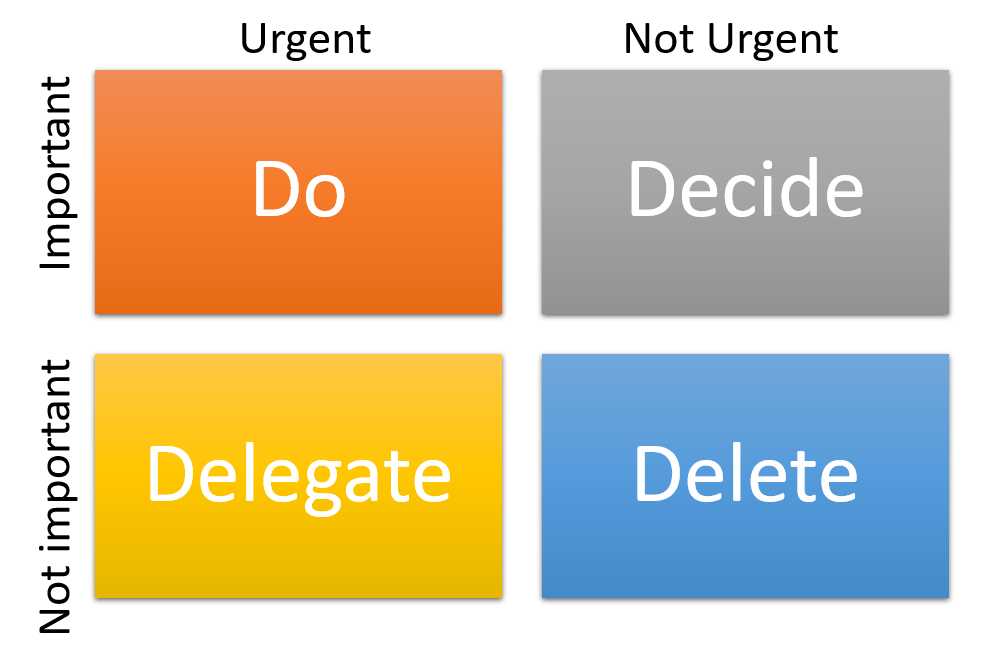

4.3.1 The Eisenhower Matrix

Using this method, you divide every task into one of four different quadrants as shown in Figure 4.3). Once you have decided where a task sits, you can decide how to handle it.

FIGURE 4.3: The Eisenhower Matrix helps you decide how important the different tasks are, and then how to deal with them. Prioritising tasks will be difficult at first, but as you get busier it will become essential for you to unsure that you accomplish all of the work to complete your PhD.

- Urgent and Important: Do this right away as it is likely to impact on other goals.

- Important but Not Urgent: Schedule such tasks into your calendar.

- Urgent but Not Important: Depending on how busy your calendar is, you might want to consider asking someone else to help with these tasks.

- Neither Urgent nor Important: You won’t have time to do these tasks when you are busy, so keep them in a list for when times are less intense.

4.3.2 The Pomodoro Technique

This is a time management method that breaks work into focused 25 minute intervals, called “Pomodoros”. These are then followed by short five minute breaks. Once you have completed four Pomodoros, you can take a longer break of 15-30 minutes. The technique is said to help improve focus, reduce distractions, and prevent burnout by encouraging regular breaks while maintaining a structured approach to work. It is particularly effective for managing tasks that require sustained attention like thesis writing.

This might be especially useful if there are a group of your who all time your Pomodoros together. You get the reward of sharing the breaks, plus the calm during those concentrated efforts.

4.3.3 SMART goals

You are likely to find SMART goals everywhere, as they are a very popular way ensuring that goals are met, including time management. Originating in 1981, SMART goals were first conceived as a framework for setting clear and achievable goals in management contexts (Doran, 1981). They are now used practically everywhere and are well worth knowing about:

- Specific: Clearly define the goal with a detailed and focused objective.

- Measurable: Ensure the goal can be quantified or tracked with specific metrics.

- Achievable: Set a realistic and attainable goal given available resources and constraints.

- Relevant: Align the goal with broader objectives and ensure it is meaningful and valuable.

- Time-bound: Set a clear deadline or time-frame to accomplish the goal.

I will not go into SMART goals in detail here, but there is plenty to read including books by Stevens (2013) and Hyatt (2023).

4.3.4 Batch tasking

You may find that your to-do list contains a number of similar tasks that would be better if performed together. For example, you may need to make five different telephone calls in relation to different parts of your studies. By batching these calls together into one of your 40 minute task slots it will ensure that you get them all done without eating into other productive time.

4.3.5 Saying no

As you get deeper into your PhD studies, you will get busier and your time will get tighter. You should know when these periods are coming up (from your whole period planning), and this will allow you to get ready for them. As you become better known in your institution, you’ll also find that people start asking you to do extra tasks. These could be favours for friends, or special assignments for your advisor. When you are asked to do these extra tasks you should take the time to look at your calendar and ask yourself where that extra time is going to come from. If you are in your busiest time and the deadline is before that ends, then you might have to say no. However, if your calendar is more open you can replace some of your activities with the task so that you can achieve it.

You do need to be clear to yourself and the person you are doing the task for exactly what the task is, when is the deadline and how much time it will take you, and what you won’t be doing during that period in order to do the extra task.

Many such tasks are worthwhile, and it may well be in your interest to find the time to do them. Your calendar should be helping you to commit time, not making your time allocation so rigid that you have to say no to everything.

4.3.6 Delegation

During your busiest times it may be that you will not be able to complete all of the tasks that you have listed. For example, you might need to attend a conference but your experimental plants still need to be watered and tended to. Use your whole period planning to identify when these periods are likely to be, and alert your advisor well ahead of time (2 - 3 months). You should be able to come up with a solution so that you can go to the conference (or other task) while someone else looks after your experiment. However, that person may well need training, hence you will need to flag this and organise for cover well in advance.

4.4 Don’t stop managing your time

Once you have learned how to manage your time, you should find that this is a useful life-skill that you can take with you after you complete your PhD. Most importantly, it will empower you to have free time that you can devote to yourself and your family and friends. The next chapter takes these planning and managing ideas to planning ahead for your future.